Ms Snyder Art Teacher Berlin Germany American High School 70s

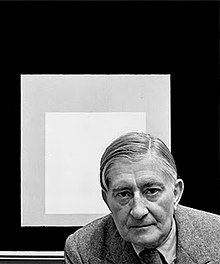

| Josef Albers | |

|---|---|

Albers in forepart of one of his Homage to the Square paintings | |

| Born | (1888-03-xix)March nineteen, 1888 Bottrop, Westphalia, Germany |

| Died | March 25, 1976(1976-03-25) (aged 88) New Haven, Connecticut |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Königliche Bayerische Akademie der Bildenden Kunst |

| Known for | Abstract painting, study of color |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Geometric brainchild |

| Spouse(s) | Anni Albers (grand. 1925) |

| Website | https://albersfoundation.org/ |

Josef Albers (; German: [ˈalbɐs]; March xix, 1888 – March 25, 1976)[1] was a German-born artist and educator. The first living artist to be given a solo shows at MoMa[ii] and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,[iii] he taught at the Bauhaus and Blackness Mountain College, headed Yale Academy's department of design, and is considered one of the most influential teachers of the visual arts in the twentieth century.

As an artist, Albers worked in several disciplines, including photography, typography, murals and printmaking. He is best known for his work as an abstract painter and a theorist. His book Interaction of Color was published in 1963.

Biography [edit]

Josef Albers, Rosa mystica ora pro nobis, 1918 (reconstruction, original destroyed c. 1944)[4]

German years [edit]

Determinative years in Westphalia [edit]

Albers was born into a Roman Cosmic family of craftsmen in Bottrop, Westphalia, Germany in 1888. His male parent, Lorenzo Albers, was variously a housepainter, carpenter, and handyman. His mother came from a family of blacksmiths. His childhood included applied grooming in engraving glass, plumbing, and wiring, giving Josef versatility and lifelong confidence in the handling and manipulation of diverse materials.[5] [6] He worked from 1908 to 1913 as a schoolteacher in his home town; he likewise trained as an fine art teacher at Königliche Kunstschule in Berlin, Germany, from 1913 to 1915. From 1916 to 1919 he began his piece of work as a printmaker at the Kunstgewerbschule in Essen, where he learnt stained-glass making with Dutch creative person Johan Thorn Prikker.[7] In 1918 he received his beginning public commission, Rosa mystica ora pro nobis, a stained-glass window for a church in Bottrop.[v] In 1919 he moved to Munich, Germany, to study at the Königliche Bayerische Akademie der Bildenden Kunst, where he was a student of Max Doerner and Franz Stuck.[8]

Entry into the Bauhaus [edit]

Albers enrolled every bit a educatee in the preliminary course (vorkurs) of Johannes Itten at the Weimar Bauhaus in 1920. Although Albers had studied painting, it was equally a maker of stained glass that he joined the faculty of the Bauhaus in 1922, approaching his chosen medium as a component of architecture and as a stand-lonely art grade.[9] The director and founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, asked him in 1923 to teach in the preliminary form 'Werklehre' of the department of design to introduce newcomers to the principles of handicrafts, because Albers came from that background and had advisable practise and knowledge.

In 1925, the twelvemonth the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, Albers was promoted to professor. At this time, he married Anni Albers (née Fleischmann) who was a student at the institution. His piece of work in Dessau included designing furniture and working with glass. As a younger teacher, he was teaching at the Bauhaus amid established artists who included Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee. The so-chosen "form master" Klee taught the formal aspects in the glass workshops where Albers was the "crafts master"; they cooperated for several years.

Emigration to the U.s.a. [edit]

Blackness Mount College [edit]

With the closure of the Bauhaus under Nazi pressure in 1933 the artists dispersed, most leaving the country. Albers emigrated to the U.s.. The architect Philip Johnson, then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, arranged for Albers to be offered a job as head of a new fine art school, Black Mountain College, in North Carolina.[ten] In November 1933, he joined the kinesthesia of the college where he was the head of the painting program until 1949.

At Black Mountain, his students included Ruth Asawa, Ray Johnson, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, and Susan Weil. He also invited of import American artists such as Willem de Kooning, to teach in the summer seminar. Weil remarked that, as a teacher, Albers was "his ain academy". She said that Albers claimed that "when you're in school, you're non an creative person, you're a student", although he was very supportive of cocky-expression when one became an artist and began on her or his journey.[11] Albers produced many woodcuts and leaf studies at this fourth dimension.

Yale University [edit]

In 1950, Albers left Black Mountain to head the department of pattern at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. While at Yale, Albers worked to expand the nascent graphic pattern program (so called "graphic arts"), hiring designers Alvin Eisenman, Herbert Matter, and Alvin Lustig.[12] Albers worked at Yale until he retired from instruction in 1958. At Yale, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Eva Hesse,[13] Neil Welliver, and Jane Davis Doggett[14] [xv] were notable students.

In 1962, as a swain at Yale, he received a grant from the Graham Foundation for the Advanced Studies of Fine Arts for an showroom and lecture on his work. Albers also collaborated with Yale professor and architect King-lui Wu in creating decorative designs for some of Wu'south projects. Among these were distinctive geometric fireplaces for the Rouse (1954) and DuPont (1959) houses, the façade of Manuscript Lodge, one of Yale'southward underground senior groups (1962), and a design for the Mt. Bethel Baptist Church (1973). Also, at this fourth dimension he worked on his structural constellation pieces.

As well during this fourth dimension, he created the abstract album covers of band leader Enoch Light'south Command LP records. His album cover for Terry Snyder and the All Stars 1959 album, Persuasive Percussion, shows a tightly packed grid or lattice of modest black disks from which a few wander upward and out as if stray molecules of some light gas.[xvi] He was elected a Swain of the American University of Arts and Sciences in 1973.[17] Albers continued to pigment and write, staying in New Haven with his wife, textile creative person Anni Albers, until his death in 1976.

Command Records [edit]

Josef Albers produced anthology covers for over 3 years between 1959 and 1961, Albers' seven album sleeves for Control Records incorporated elements such equally circles and grids of dots, highly uncommon in his practice. "The serial of records made by Control Records over half a century ago still resonate with audiophiles today, and are much sought-after by connoisseurs of mid-century modern design for their hitting covers. This was all due to the collaboration between two individuals, Josef Albers and Enoch Lite. Both men — i an influential teacher and artist, the other a stereo-recording pioneer — driven by strong convictions and passion for their respective crafts."

Works [edit]

Homage to the Foursquare [edit]

Accomplished as a designer, lensman, typographer, printmaker, and poet, Albers is best remembered for his work as an abstruse painter and theorist. He favored a very disciplined approach to limerick, especially in the hundreds of paintings and prints that brand up the series Homage to the Square. In this rigorous series, begun in 1949, Albers explored chromatic interactions with nested squares. Usually painting on Masonite, he used a palette knife with oil colors and oftentimes recorded the colors he used on the back of his works. Each painting consists of either three or iv squares of solid planes of colour nested within one another, in one of four different arrangements and in square formats ranging from 406×406 mm to 1.22×1.22 m.[eighteen]

Murals [edit]

Albers Wrestling (1977) in Sydney

In 1959, a gold-leaf landscape by Albers, Two Structural Constellations was engraved in the anteroom of the Corning Glass Building in Manhattan.[19] For the entrance of the Fourth dimension & Life Building entrance hall, he created Two Portals (1961), a 42-anxiety by 14-feet mural of alternate glass bands in white and chocolate-brown that recede into 2 bronze centers to create an illusion of depth.[20] In the 1960s, Walter Gropius, who was designing the Pan Am Edifice with Emery Roth & Sons and Pietro Belluschi, commissioned Albers to make a landscape. The artist reworked City, a sandblasted glass construction that he had designed in 1929 at the Bauhaus, and renamed it Manhattan. The giant abstract mural of black, white, and scarlet strips arranged in interwoven columns stood 28-anxiety high and 55-anxiety broad and was installed in the lobby of the building; it was removed during a lobby redesign effectually 2000. Before he died in 1976, Albers left exact specifications of the piece of work so that it could easily exist replicated; in 2019, it was replicated and reinstalled in its original identify in the Pan Am building, now renamed MetLife.[21] [22] In 1967, his painted landscape Growth (1965) as well every bit Loggia Wall (1965), a brick relief, were installed on the campus of the Rochester Institute of Technology. Other architectural works include Gemini [23](1972), a stainless steel relief for the Chiliad Artery National Bank lobby in Kansas Metropolis, Missouri, and Reclining Effigy (1972), a mosaic mural for the Celanese Building in Manhattan destroyed in 1980. At the invitation of a onetime educatee, the Australian architect Harry Seidler, Albers designed the landscape Wrestling (1976) for the Mutual Life Centre in Sydney.

Color theory [edit]

In 1963, Albers published Interaction of Color, which is a record of an experiential way of studying and teaching colour. He asserted that color "is almost never seen as it really is" and that "colour deceives continually", and he suggested that colour is all-time studied via experience, underpinned by experimentation and observation. The very rare first edition has a express printing of only 2,000 copies and contained 150 silk screen plates. This piece of work has since been republished, and is at present available as an iPad App.[24]

Colour model representing Albers' color theory as described in Interaction of Colour (1963)

Albers presented color systems at the end of his courses (and at the stop of 'Interaction of Colour') and these featured descriptions of primary, secondary and third color, as well as a range of connotations that he assigned to specific colors on his triangular color model.[25]

In respect to his artworks, Albers was known to meticulously list the specific manufacturer's colours and varnishes he used on the dorsum of his works, equally if the colours were catalogued components of an optical experiment.[26] His work represents a transition between traditional European art and the new American art.[27] It incorporated European influences from the Constructivists and the Bauhaus motion, and its intensity and smallness of calibration were typically European,[27] merely his influence fell heavily on American artists of the late 1950s and the 1960s.[27] "Hard-edge" abstract painters drew on his use of patterns and intense colors,[28] while Op artists and conceptual artists further explored his interest in perception.[27]

In an commodity about the artist, published in 1950, Elaine de Kooning concluded that even so impersonal his paintings might at offset appear, not one of them "could have been painted by any one just Josef Albers himself.".[five]

Teaching and influence [edit]

Although Albers prioritized teaching his students principles of color interaction, he was admired by many of his students for instilling a general approach to all materials and ways of engaging information technology in design. Albers "put exercise earlier theory and prioritised experience; 'what counts,' he claimed 'is not and so-called knowledge of so-chosen facts, only vision – seeing.' His focus was procedure."[29] Although their relationship was often tense, and sometimes, even combative, Robert Rauschenberg after identified Albers as his most important teacher.[thirty] Albers is considered to be ane of the almost influential teachers of visual art in the twentieth century.[31]

Noted students of Albers [edit]

- Richard Anuszkiewicz (painter)

- Ruth Asawa (sculptor)

- Varujan Boghosian (collage artist and sculptor)

- Norman Carlberg (sculptor, educator)

- Jane Davis Doggett (graphic designer)

- Robert Engman (sculptor)

- Erwin Hauer (sculptor)

- Gerald Garston (painter)

- Eva Hesse (sculptor)

- A. B. Jackson (painter)

- Robert L. Levers, Jr. (1930-1992; painter, Professor of Fine Arts, University of Texas, Austin)

- Jay Maisel (photographer)

- Ronald Markman (painter and sculptor)

- Victor Moscoso (graphic artist)

- Charles O. Perry (sculptor)

- Irving Petlin (painter)

- Joseph Raffael (painter)

- Robert Rauschenberg (painter and sculptor)

- Robert Reed (painter, educator)

- William Reimann (sculptor, educator)

- Irwin Rubin (construction and collage artist, educator)

- Stephanie Scuris (sculptor, educator)

- Arieh Sharon (builder)

- Harry Seidler (builder)

- Richard Serra (sculptor)

- Sewell Sillman (painter, educator)

- Robert Slutzky (1929–2005) painter, teacher of painting and architecture

- Julian Stanczak (painter)

- Cora Kelley Ward (painter)

- Neil Welliver (painter)

Quotes of the creative person [edit]

- – "Every perception of color is an illusion.. ..we do not see colors as they really are. In our perception they alter one another."[32] [c. 1949, when Albers started his outset Homage to the Square paintings]

- – "THE ORIGIN OF Art: The discrepancy between concrete fact and psychic effect. THE CONTENT OF Art: Visual information of our reaction to life. THE MEASURE OF Art: The ratio of effort to event. THE AIM OF ART: Revelation and evocation of vision."[33] [1964, from his text "Homage to the square"]

- – "For me, abstraction is real, probably more than existent than nature. I'll go further and say that abstraction is nearer my heart. I adopt to see with closed eyes."[32] [1966]

- – "Fine art is not to be looked at. Art is looking at united states.. .To be able to perceive information technology we need to be receptive. Therefore art is at that place where art meets u.s. now. The content of fine art is visual formulation of our relation to life. The mensurate of art, the ratio of attempt to consequence, the aim of fine art revelation and evocation of vision.[34] [1968, in oral history interview with Josef Albers]

- – "I made true the first English sentence [Albers came from Federal republic of germany] that I uttered (ameliorate stuttered) on our arrival at Black Mount College in November 1933. When a student asked me what I was going to teach I said: 'to open optics'. And this has become the motto of all my education."[35] [1970, in 'A conversation with Josef Albers']

Exhibitions (not a complete listing) [edit]

Solo [edit]

- In 1936, Albers was given his first solo testify in Manhattan at J. B. Neumann's New Art Circle.[36] [37]

- The Graphic Constructions of Josef Albers (Dec 8, 1969—February 24, 1970) MOMA, New York[two]

- Josef Albers at The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Exhibition of His Paintings and Prints (Nov 19, 1971—Jan 11, 1972) Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan.[3]

Grouping [edit]

- documenta I (1955) and documenta IV (1968) in Kassel.

- The Responsive Heart (1965) A major Albers exhibition, organized by the Museum of Modernistic Art, traveled in South America, Mexico, and the U.s. from 1965 to 1967.[38]

Posthumous [edit]

- Josef Albers, 1888–1976 (Mar 26—Apr 19, 1976) MoMa, New York[39]

- The photographs of Josef Albers: a selection from the collection of the Josef Albers Foundation (January 27—Apr 19, 1988) MoMa, New York[40]

- Painting on paper – Josef Albers in America (2010) Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; Centre Pompidou, Paris, and The Morgan Library & Museum, Manhattan. 80 oil works on newspaper, many never previously exhibited.[41]

- Josef Albers (2011) Palazzina dei Giardini, Modena, Italian republic[5]

- Albers and Heirs: Josef Albers, Neil Welliver, and Jane Davis Doggett (2014) Elliott Museum, Florida[fifteen]

- Ane and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers (Nov 23, 2016—Apr two, 2017) MoMa, New York[42]

- Josef Albers in Mexico (Nov three, 2017—Apr 4, 2018) Guggenheim Museum, New York[43]

- Albers and Morandi: Never Finished: works by Josef Albers and Giorgio Morandi (2021) David Zwirner Gallery, New York[44]

Legacy [edit]

The Josef Albers papers, documents from 1929 to 1970, were donated by the artist to the Smithsonian Institution'south Athenaeum of American Art in 1969 and 1970. In 1971 (near five years earlier his death), Albers founded the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation,[45] a nonprofit system he hoped would further "the revelation and evocation of vision through art". Today, this system serves every bit the office for the estates of both Josef Albers and his wife Anni Albers, and supports exhibitions and publications focused on the works of both artists. The foundation building is located in Bethany, Connecticut, and "includes a central research and archival storage heart to adjust the Foundation'due south fine art collections, library and archives, and offices, equally well every bit residence studios for visiting artists."[46] A second, and substantial, office of the Josef Albers manor is held past the Josef Albers Museum in Bottrop, Deutschland, where he was born.[47] Both institutions continue agile outreach to secure the artist's reputation.

In 2019, his "colossal" landscape, Manhattan, was reinstalled at the Walter Gropius-designed 200 Park Avenue (Metlife) Building, New York, following an almost two decade absenteeism. "While we appreciate its importance in the art community, information technology simply doesn't work for u.s.a. anymore," a Metlife representative is quoted as saying, at the time of its removal (2000).[48] Two decades later, the piece is over again being hailed as the vibrant centerpiece of the building, with the Albers Foundation's director on hand for the rededication of the piece of work: "This is what fine art was for him: something that could affect you, peradventure gave a trivial bit of joy to the lives of those people rushing to their trains or rushing out of the station to their workday."[49]

Criticism [edit]

Josef Albers' volume Interaction of Colour continues to be influential despite criticisms that arose following his death. In 1981, Alan Lee attempted to refute Albers' full general claims about color feel (that color deceives continually) and to posit that Albers' organisation of perceptual didactics was fundamentally misleading.

Lee examined iv topics in Albers' account of color critically: In additive and subtractive colour mixture; the tonal relations of colours; the Weber-Fechner Police force; and simultaneous dissimilarity. In each example Lee suggested that Albers made fundamental errors with serious consequences for his claims about colour and his pedagogical method. Lee suggested that Albers' belief in the importance of color deception was related to a misconception about artful appreciation (that it depends upon some kind of confusion about visual perception). Lee suggested that the scientific colour hypothesis of Edwin H. Land should be considered in lieu of the concepts put forward by Albers. Finally, Lee called for a reassessment of Albers' art every bit necessary, following successful challenge to the foundational colour concepts that were the basis of his corpus.[50] [51]

Dorothea Jameson has challenged Lee'due south criticism of Albers, arguing that Albers' arroyo toward painting and pedagogy emphasized artists' experiences in the handling and mixing of pigments, which often have different results than predicted by color theory experiments with projected light or spinning color disks. Furthermore, Jameson explains that Lee'southward own understanding of additive and subtractive colour mixtures is flawed.[52]

Value on the art market place [edit]

Several paintings in Albers's series Homage to the Square have outsold their estimates, including Homage to the Square: Joy (1964) which sold for $ane.five million (nearly double its judge) at a 2007 sale at Sotheby's.[53] In 2015, Written report for Homage to the Foursquare, R-Iii E.B. (1970) sold for £785,000 (well above the estimated £350,000–450,000), at "the high point of an agile market."[54]

Albers, a prolific creative person, has numerous prints and drawings available outside of the museums where his piece of work is represented.

The Albers Foundation, the main casher of the estates of both Josef and Anni Albers, remains protective of the artist's work and reputation. In 1997, one twelvemonth later on the auction firm, Sotheby'southward, bought the Andre Emmerich Gallery, the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation did non renew its iii-yr contract with the gallery.[55] The Foundation has as well been instrumental in exposing fakes.[5]

See also [edit]

- The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation

- Bauhaus

- Architype Albers (large typeface based on Albers' 1927–1931 experimentation with geometrically synthetic stencil types for posters and signs)

References [edit]

- ^ "Josef Albers, Creative person and Teacher, Dies". The New York Times. March 26, 1976. p. 33. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ a b "The Graphic Constructions of Josef Albers | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art . Retrieved Jan xix, 2022.

- ^ a b "Notes". Homage to the Square: Soft Spoken. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1969.

- ^ Albers, Josef (1917–1918). "Rosa Mystica Ora Pro Nobis (reconstruction 2011)". St. Michael'due south Church building, Bottrop, Germany: Albers Foundation Facebook Page. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Morris, Roderick Conway (Oct 21, 2011). "Making of a Bauhaus Chief". The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-03-29

- ^ "Josef Albers, Creative person and Teacher, Dies". The New York Times. March 26, 1976. Retrieved 2020-03-29

- ^ de Melo, M. (2019) Mosaic every bit an Experimental System in Gimmicky Art Practice and Criticism. PhD Thesis: University for the Creative Arts; University of Brighton, p.111

- ^ Josef Albers Archived Nov 4, 2013, at the Wayback Automobile Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville.

- ^ Kingdom of the netherlands Cotter (July 26, 2012), Harmony, Harder Than Information technology Looks – 'Josef Albers in America: Painting on Newspaper,' at the Morgan The New York Times.

- ^ Pepe Carmel (June 25, 1995), A Modernistic Chief of Bottles, Scraps and Squares The New York Times.

- ^ Robert Ayers (March 29, 2006). "Susan Weil". Art+Auction. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Rob Roy Kelly (June 23, 1989). "Origins: Yale years". Retrieved February nine, 2010.

- ^ "Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Teaching | Tate". Tate Etc . Retrieved August xi, 2017.

- ^ "Josef Albers and Heirs showroom on view at The Elliott Museum in Florida". Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Elliott Museum presents 'Albers & Heirs: Josef Albers, Neil Welliver, and Jane Davis Doggett'". Martin County Times. Martincountytimes.com. November 9, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Masheck, Joseph (December 2010 – January 2010). "ALBERS' Record JACKETS: Doing an Artful Job". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American University of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April six, 2011.

- ^ Josef Albers Museum of Mod Art, Manhattan

- ^ "Josef Albers Chronology". The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation.

- ^ David Due west. Dunlap (June 17, 2002), Printing 'L' for Landmark; Time & Life Lobby, a l's Gem, Awaits Recognition The New York Times.

- ^ Carol Vogel (July 9, 2001), A Familiar Mural Finds Itself Without a Wall The New York Times.

- ^ "Josef Albers's Manhattan returns to its rightful place in the MetLife building". September 23, 2019.

- ^ Geismar, Daphne. "The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation". The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Interaction of Color on the App Store". Retrieved April nineteen, 2022.

- ^ Albers, Josef (1963). Interaction of Color. New Haven and London: Yale Academy Printing. ISBN978-0300018462.

- ^ Josef Albers: February 28 — March 27, 2007 Waddington Custot Galleries, London.

- ^ a b c d Piper, David. The Illustrated History of Art, ISBN 0-7537-0179-0, p469.

- ^ Piper, David. The Illustrated History of Art, ISBN 0-7537-0179-0, p470.

- ^ Saletnik, Jeffrey (2007). "Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the Imperative of Pedagogy". Tate Papers. London: The Tate Gallery. ISSN 1753-9854.

- ^ Christopher Knight (May 14, 2008), Robert Rauschenberg, 1925 – 2008: He led the way to Pop Fine art Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Sandler, Irving (Jump 1982). "The School of Fine art at Yale; 1950-1970: The Collective Reminiscences of Twenty Distinguished Alumni". Fine art Journal. 42, No. 1 (The Didactics of Artists): xiv–21. doi:10.2307/776486. JSTOR 776486.

- ^ a b "Josef Albers - Wikiquote".

- ^ "Josef Albers - Wikiquote".

- ^ https://www.aaa.si.edu/download_pdf_transcript/ajax?record_id=edanmdm-AAADCD_oh_214202[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ "Josef Albers - Wikiquote".

- ^ Josef Albers Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Auto Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- ^ J.B. Neumann Papers in The Museum of Modernistic Art Archives

- ^ "The Responsive Eye | MoMA". The Museum of Mod Art . Retrieved Jan 19, 2022.

- ^ "Josef Albers, 1888–1976 | MoMA". The Museum of Mod Fine art . Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "The Photographs of Josef Albers: A Pick from the Drove of The Josef Albers Foundation | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art . Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "Josef Albers in America: Painting on Paper: July 20 through October 14, 2012". The Morgan Library & Museum. 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ "One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art . Retrieved January nineteen, 2022.

- ^ "Guggenheim Museum Presents Josef Albers in United mexican states". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation . Retrieved Feb 16, 2022.

- ^ Schjeldahl, P. (2021). "Albers and Morandi". The New Yorker. Vol. v. 97, n. 2. p. five.

- ^ The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation website Archived July viii, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation: Mission Argument Archived July 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Josef Albers Archived June 23, 2012, at the Wayback Auto Fondation Beyeler, Riehen.

- ^ Stoilas, Helen (September 23, 2019). "Josef Albers's Manhattan returns to its rightful place in the MetLife building". The Art Newspaper - International fine art news and events . Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Coleman, Nancy (September 23, 2019). "Once Removed and Destroyed, a Modernist Landscape Makes Its Render". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Alan. "A Critical Business relationship of Some of Josef Albers' Concepts of Color." Leonardo (1981): 99–105.

- ^ Jameson, Dorothea. "Some Misunderstandings most Color Perception, Color Mixture and Colour Measurement". Leonardo, vol. xvi, no. 1, 1983, pp. 41–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1575043.

- ^ Jameson, Dorothea. Some Misunderstandings near Color Perception, Color Mixture and Color Measurement. Leonardo, vol. 16, no. 1, 1983, pp. 41-42. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1575043.

- ^ J.South. Marcus (December xviii, 2010), Re-Examining a Famed Teacher The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Crichton-Miller, Emma (November 11, 2016). "Jubilant Bauhaus artists Josef and Anni Albers". Fiscal Times . Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Carol Vogel (Oct 3, 1997), Sotheby's Loses Albers Manor The New York Times.

Further reading [edit]

- Albers, Josef (1975). Interaction of Colour. New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-11595-half dozen.

- Bucher, François (1977). Josef Albers: Despite Straight Lines: An Analysis of His Graphic Constructions . Cambridge, MA: MIT Printing.

- Danilowitz, Brenda; Fred Horowitz (2006). Josef Albers: to Open Eyes : The Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Yale. Phaidon Press. ISBN978-0-7148-4599-9.

- Darwent, Charles: Josef Albers: life and work, London: Thames & Hudson, [2018], ISBN 978-0-500-51910-3

- Diaz, Eva (2008). "The Ethics of Perception: Josef Albers in the Us". Volume XC Number 2 (June): The Fine art Bulletin.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Harris, Mary Emma (1987). The Arts at Black Mountain College . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Weber, Nicholas Fox; Licht, Fred (1988). Josef Albers: A Retrospective (exh. cat.) . New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. ISBN978-0-8109-1876-iv.

- Weber, Nicholas Play a trick on; Licht, Fred; Danilowitz, Brenda (1994). Josef Albers: Drinking glass, Color, and Light (exh. true cat., Peggy Guggenheim Drove, Venice). New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications. ISBN978-0-8109-6864-vi.

- Wurmfeld, Sanford; Rector, Neil 1000.; Ratliff, Floyd (August 1, 1996). Color Function Painting: The Art of Josef Albers, Julian Stanczak and Richard Anuszkiewicz. Contemporary Collections. ISBN978-0-9720956-0-0.

- Cleaton-Roberts, David; Fox Weber, Nicholas; Williams, Graham; Harrison, Michael (2012). Abstruse Impressions: Josef Albers, Naum Gabo, Ben Nicholson. London: Alan Cristea Gallery. ISBN978-0-9569203-five-5.

External links [edit]

- The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation

- Art Signature Dictionary, examples of genuine signatures by Josef Albers

- Brooklyn Rail, tape jacket

- Cooper Hewitt Museum Exhibition, 2004

- Josef Albers collection at the Israel Museum.

- Josef Albers Guggenheim Museum

- Josef Albers at the Museum of Mod Art

- Josef Albers, National Gallery of Australia, Kenneth Tyler Collection

- Tate Modern exhibition, London 2006

- "Bauhaus in Mexico", article about the Albers, their trips to Mexico, and the Guggenheim bear witness in 2018. The New York Review of Books, February 25, 2018

- "Josef Albers Papers, 1933–1961", The Frick Collection/Frick Fine art Reference Library Archives.

- Josef Albers Papers (MS 32). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

Athenaeum of American Fine art collection:

- An Oral History interview with Josef Albers, 1968 June 22 – July v

- Josef Albers letters to J. B. Neumann, 1934–1947

- A Finding Aid to the Josef Albers papers, 1929–1970 in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Establishment

Works past Josef Albers

- Brooke Alexander Gallery

- Google images; many pictures of the artworks made by Albers

- Google images; many pictures of the artworks made past Albers

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josef_Albers

Post a Comment for "Ms Snyder Art Teacher Berlin Germany American High School 70s"